“If I can make it there/ I’ll make it anywhere.”

I love New York. And London. And LA. But they’re really provincial. The Bay Area’s even worse.

Lots of technical diversity (people come from different ethnic backgrounds), very little diversity in thought. And that leads to the easiest of all intellectual mistakes to make: confirmation bias. Confirmation Bias happens when you are so confident in what you believe that you’re unwilling to test the validity of your ideas. Warren Buffett (who does not live in any of those places) puts it this way: “What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact.” And nothing will kill your social media faster than confirmation bias.

People who live in big cities tend to think that big cities are where all the smart people live. People who went to prestigious universities tend to think that’s where all the smart people go. Both may be true, measured by test scores. If you’re looking for the right place to convene a MENSA meeting, a large city with a great university is a great idea. However, if you’re trying to understand what a customer will like, what your personal peer group thinks is irrelevant.

I spent 10 years in show business, and one of the iron rules that you can’t avoid is “Know your audience.” Most of the time that I worked in the comedy business, I was not in the audience. Adam Sandler is an extremely successful movie actor. I haven’t seen any of his pictures, and don’t plan to. Take a look some time at the Top Ten TV Shows or the Top Ten Movies. How many have you seen? How many of them are made for people like you? How many of them would you have put money behind?

When I worked in the Agricultural Media, you can bet I wasn’t in the audience. My complete ignorance of agriculture made for a great competitive advantage—I had to shut up and listen to the damn customer. I couldn’t fake my way through a conversation about soybeans. And if your publishing is going to be any good, you have to have the same kind of discipline.

Right now, I am in the audience for a certain kind of content—NPR, The Wall Street Journal, Harvard Business Review, The Economist. I went to Harvard and Wharton. I worked at McKinsey and have served clients all over the world. Those content brands are for people like me. If you were to ask me to pick mainstream sitcoms, I would fail. Not because I’m better than other people, but because I don’t know what the mainstream wants. I am not the mainstream. And neither are you. I have no particular insight into what most TV watchers would like, because I don’t watch sitcoms. Yet every year, thousands of businesses fail because they don’t understand what their target segment wants or needs. Companies starting in New York or Silicon Valley may have a talent advantage. There’s no doubt, the average standardized test scores are higher there. But they have an endemic confirmation bias that has to be explicitly managed.

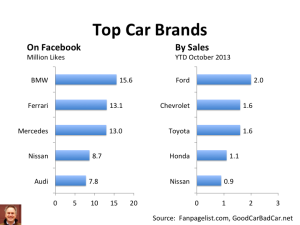

Take driverless cars. I think we all understand the appeal of efficiency and convenience that comes from on-demand transportation. And it makes perfect sense if you live in a big city, where parking is inconvenient and expensive, the local stores are walkable, and car ownership is seen as a little self-indulgent. I live in Omaha. Parking is free and (usually) easy to get. Local stores are assuredly not walkable. And cars are the only way to get my kids to school, baseball, and dance. And there are tens of millions of people like me across America—in Omaha, Phoenix, San Antonio, Jacksonville, et al. But when you have a community of people in Palo Alto talking to their peers on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, it’s hard to see an opposing view. We all want to believe that what we personally think is a mainstream view. It rarely is. Suburbanites and Rural Americans have very emotional attachments to their cars. And that emotional tie is very different from the utilitarian way urbanites tend to view cars.

Another favorite example is building high-speed rail. Rail makes perfect sense in Western Europe, which is densely populated, has severely limited parking in cities, and very high fuel prices. And if you live in Boston, New York, or Washington DC, it may make a lot of sense. But the travel experience of most Americans is not like the travel experience of urban residents in the Northeast. La Guardia is awful. So is O’Hare. And Logan isn’t much better. If I were flying between those three airports regularly (and all my friends were too), I would be convinced that our air travel system is fatally flawed. But lots of people don’t fly through those airports, and have a very different emotional reaction to air travel.

In the excellent book How Children Succeed, Paul Tough cites an ingenious experiment by Peter Wason that underscores our desire to be proven right. You should read the whole thing, but the crux is this:

“It feels much better to find evidence that confirms what you believe to be true than to find evidence that falsifies what you believe to be true. Why go out in search of disappointment?”

So what does this have to do with your Publishing? Everything.

The content you publish needs to be clearly connected to the products you make, the value deliver, and your understanding of the landscape. If your thinking about your segment and your market is flawed, your publishing will never succeed, no matter how gifted your blogger or social media manager. You need to inhabit the space your target market lives in.

As strategists and business owners, you have to go through the painful experience of watching your favorite ideas die. If you don’t push your thinking hard, you will create mediocre content. Test your hypotheses. That means going more than 50 miles out of town. That means immersing yourself in the world of your target market. Knowing what they eat for lunch, how they define success, and what their own confirmation bias is. (Nothing will endear you more to your target segment than understanding their emotional world—what they love and why they love them. Are your customers the Navy or a bunch of Pirates? Are they the snobs or the slobs? Are they Spago, Pizza Hut, or Domino’s?)

CNN this week announced the end of Piers Morgan’s prime time show. There’s a great summary here in the New York Times, but the crux is this—he didn’t know his audience. He thought his audience was just like him and the other people who work at CNN—Internationalist, urban, anti-gun. Guns are a subject worth debating, but Piers and his production team showed a remarkable tin ear. They were guilty of obvious Confirmation Bias. Maybe the entire Upper West Side of Manhattan agreed with them. But the kind of people who watch CNN Primetime don’t live on the Upper West Side.

If you can make it in New York, that’s great. But plenty of things that are popular in New York have no impact on the rest of the world.

I loved my years in New York and wouldn’t trade them for anything. I hope my kids live in New York for a while when they grow up. But it’s crazy to think that living in a big city like New York or Los Angeles or San Francisco is representative of how most Americans live.

Omaha has its limitations, but at least we know we’re provincial.

Photo Credit: Flickr

Adrian Blake has worked with Saturday Night Live, McKinsey & Co., and The Progressive Farmer and is a founder of a Social Media agency.

Adrian Blake. Strategy. Social Media.