Winston Churchill was under a lot of stress.

France had just fallen to the Nazis. It was fully expected that the Germans were preparing for an invasion of the British Isles, and it was not at all clear that Britain would prevail. It was so bad that his usual stress management routine of Champagne, whisky, and cigars wasn’t working. Daily naps weren’t easy any more, and he was starting to feel the strain. Finally, one of his Cabinet Ministers mentioned that when he felt stressed, he went into his garden and painted; his troubles just fell away. Churchill, willing to try anything at this point, agreed to give it a go, and had the Minister’s painting teacher come to Chequers, the Prime Minster’s country house. The teacher and Churchill brought their easels into the garden, set up the canvases, and arranged the paints. The teacher said, “Now Mr. Prime Minister, just paint what you see.” Churchill thought hard and very carefully drew a thin and labored line, then stopped and thought hard. “Come on Mr. Prime Minister, just be free, and paint whatever you see.” Churchill added a second thin, tentative line. This cycle of encouragement and reluctance went on for some minutes until finally the teacher said: “Mr Prime Minister. Will you please hurry up and get done with your first hundred bad paintings so we can get to work on your first good one.”

This story is apocryphal but incredibly evocative. (I think I got it from Martin Gilbert’s spectacular Winston Churchill: A Life, which condenses his eight volume academic biography into one volume for the layman. He’s like the English Robert Caro.) Even Winston Churchill, arguably the greatest man of the 20th Century was afraid to be mediocre.

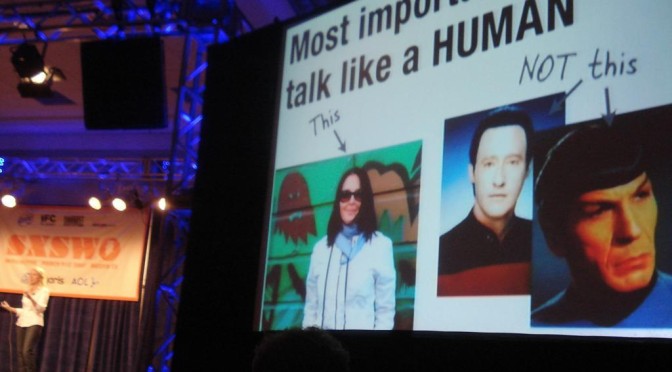

We all have a deep fear of sucking. But until we go through the phase of sucking, we will never be good. Most content creators are like Churchill in the first five minutes—tentative, afraid to commit, and not producing anything of merit. Look at the blogs and Twitter feeds in your vertical market—how many are actually taking chances and trying to do something good? It’s not that there are so many brilliant people writing blogs today—we’re still writing the rules of how to kick ass online. But most people aren’t even trying to be good. They just want to not get in trouble.

Unfortunately, the path to excellence leads through mediocrity. That’s the nature of learning new skills. We all start as beginners. Mastery by George Leonard is a great explanation of how we learn. And just like when you learned how to ice skate or type, you’re awful at first. If you don’t get serious about improving, you’ll never get better. But part of getting better is being willing to press “publish” even when your stuff isn’t that good. You should always do the best you can at any one time, but, like a 14-year-old boy asking a girl out on a date, sometimes the best you can do just isn’t any good yet.

The good news is that, when you start out, no one’s paying attention anyway—Google doesn’t care about you until you have 20 or 30 blog posts anyway, and in the early days, no one is reading your Twitter feed. Like a standup comic, you can be awful in obscurity. If you’re focused, you can make it to Page 1 of Google in a few months, but you won’t get there without taking a lot of swings.

Being bad at something hurts because we’re vulnerable. This is a terrific video from Brené Brown talking about the need to acknowledge your critics, make room for them, but not pay too much attention to them. Your job is not to make everyone love you. Your job is to show up and be in the arena every day. And sometimes that’s painful. But the only way to get past mediocrity is to go through it.

She puts it very well when she says “If you’re not in the arena also getting your ass kicked, I don’t care about your feedback.”

Don’t be afraid to write your first 20 bad blog posts. It’s the only way to get to your first good one.

Photo credit: Flickr

Adrian Blake has worked with Saturday Night Live, McKinsey & Co., and The Progressive Farmer and is a founder of a Social Media agency.

Adrian Blake. Strategy. Social Media.