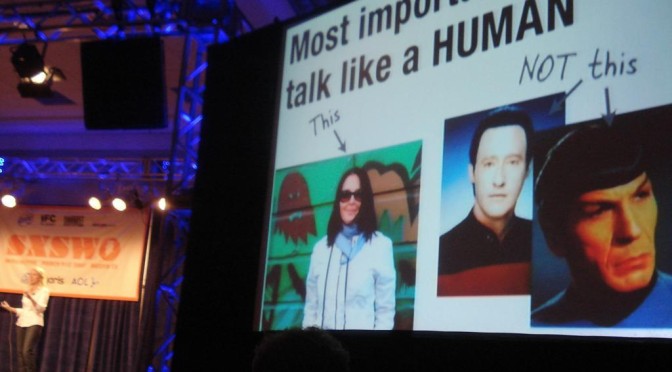

We all hate to be bad at something. As Kathy Sierra says, “The User wants to kick ass.” And most of us don’t start out kicking ass.

One solution is to embrace what Anne Lamott perfectly dubs the “shitty first draft.” I hardly need to tell you what that means, but let’s use Lamott’s words.

The first draft is the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later. You just let this childlike part of you channel whatever voices and visions come through and onto the page… Just get it all down on paper because there may be something great in those six crazy pages that you would never have gotten to by more rational, grown-up means. There may be something in the very last line of the very last paragraph on page six that you just love, that is so beautiful or wild that you now know what you’re supposed to be writing about, more or less, or in what direction you might go — but there was no way to get to this without first getting through the first five and a half pages.

This maps perfectly into Ed Catmull’s thinking, that Pixar’s entire method is to go “from suck to non-suck.”

If you’re noting a theme, you’re right. Creating content for your brand is much more about craft than art. The way to get something decent written is to start with something (anything). If you hide from the process and “wait for inspiration,” you will never accomplish anything. Your first drafts will suck. By definition. Get over it. Your first 20 completed posts will someday fill you with cringing embarrassment, just like your high school poetry. But there’s a big difference between someone who’s out there trying to create and someone who’s too afraid to try.

Does this mean you can just throw bad stuff out there? Of course not. You still have to respect your readers’ time and energy. Is any of this easy? Of course not. But if short cuts existed, you would have found them by now. If you’re afraid to step up to bat, you cannot get a base hit.

John Lennon described how he wrote Nowhere Man (for my money, the best thing he ever did).

“I’d spent five hours that morning trying to write a song that was meaningful and good, and I finally gave up and lay down. Then ‘Nowhere Man’ came, words and music, the whole damn thing as I lay down”.

Keith Richards has similarly said:

(P)eople say they write songs, but in a way you’re more the medium. I feel like all the songs in the world are just floating around, it’s just a matter of like an antenna, of whatever you pick up. So many uncanny things have happened. A whole song just appears from nowhere in five minutes, the whole structure, and you haven’t worked at all.

But if you’re not there with a guitar in your hand, the song won’t get written at all. By all means, be open to inspiration. But show up to work every day anyway. Embrace the shitty first draft and start creating. That act alone puts you ahead of most of the human race, who are still waiting for inspiration.

And read Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird. Most honest book about writing I know.

Photo Credit: Flickr

Adrian Blake has worked with Saturday Night Live, McKinsey & Co., and The Progressive Farmer and is a founder of a Social Media agency.

Adrian Blake. Strategy. Social Media.